California International Marathon ‘25 | A Reflection, 7 Years of Running

California International Marathon: 2:35:27 (PR)

Table of Contents

Introduction

CIM 2025 Overview

Reflection: Seven Years of Running

Why I Started Running

Early Races and Lessons Learned

My Marathon Journey

First Marathon and Early Mistakes

From 2:38 to 2:35

Why Sub-2:40 Is Hard (and Sub 2:30 even harder)

CIM 2025 Training Framework

Key Training Characteristics

Training Volume Progression and Load Management

Consistent Hill Work

Long Run Structure and Marathon-Specific Fatigue

Carbohydrate Intake and Fueling

Shoe Rotation and Injury Implications

Mastering the Run Commute

Lessons for Next Season

What Needs to Change

Looking Ahead to Berlin 2026

1. Introduction

June 2019 - After finishing my 2nd half marathon in 1 hr 35 mins and feeling defeated

This reflection documents my journey to the California International Marathon 2025, both as a race outcome and as the product of seven years of learning, experimentation, and adaptation. Rather than focusing on race-day strategy (see reports on Berlin 2025, CIM 2024, and Boston 2024), I focus on the long view: how consistency, self-coaching, and targeted training decisions shaped my progression from an unlikely runner in 2019 to a 2:35 marathon in 2025. Along the way, I examine what it takes to train near one’s limits while balancing injury, work, family, and life, and I reflect on the lessons that will guide the next phase of my running. This is also a celebration of continuity. As I went under for hip surgery in December 2024, I genuinely believed my running career might be over. One year later, I ran a career-best marathon.

2. CIM 2025 Overview

Figure 1: CIM 2025: Consistent 5k paces from start to finish.

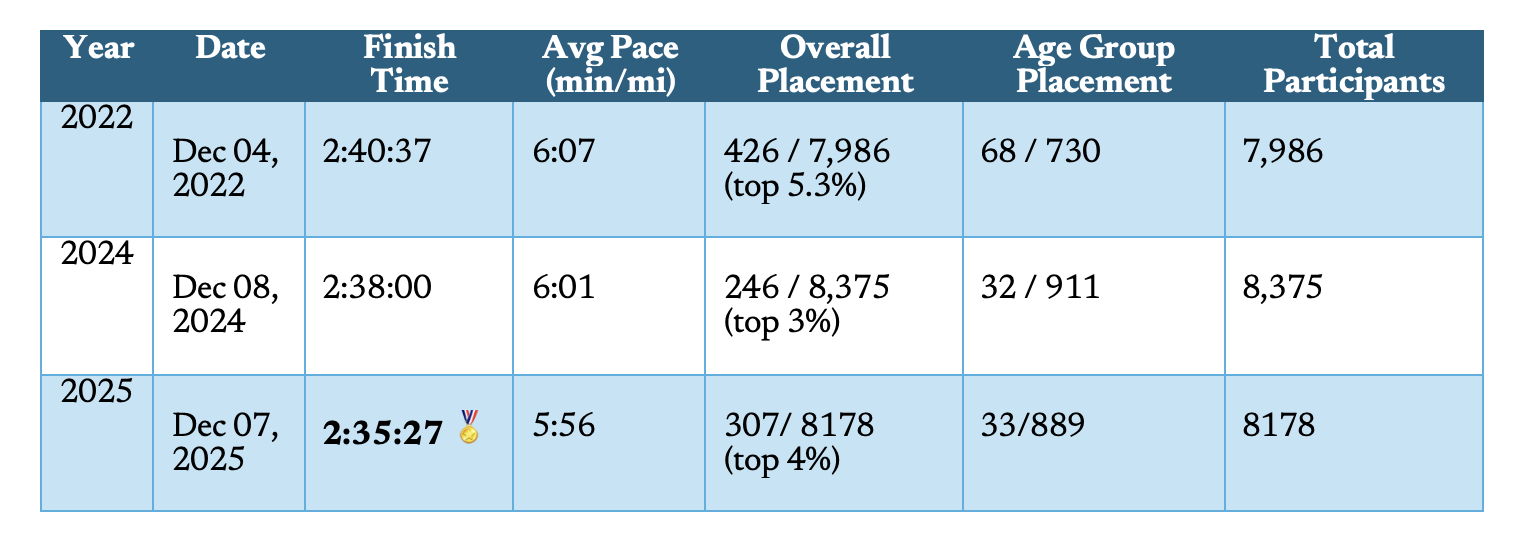

California International Marathon (CIM) 2025 unfolded almost exactly as planned, resulting in a near-perfect negative split: 1:17:30 for the first half and 1:17:58 for the second, finishing in 2:35:27 at a 5:56 pace. My target range was 2:33 to 2:35, and based on how training progressed, I knew 2:35 was realistic on race day. The clearest indicators getting into the race were my threshold pace and VO₂ max. By race week, my threshold pace had improved to 5:33 with a VO₂ max of 68. By comparison, at CIM 2024 my threshold pace was 5:45 and VO₂ max was 64, reflecting a meaningful physiological gain year over year.

CIM has earned its reputation as one of the premier PR- and Olympic Trials–qualifying marathons in the United States. The field consistently features a deep mix of elite and sub-elite athletes, competitive age-group runners chasing Boston or Trials standards, and experienced amateurs seeking fast conditions. As a result, CIM is deeper and more competitive than many large-city marathons, with a high concentration of sub-3-hour runners. This depth makes it an especially enjoyable race for me, as I am able to run alongside faster athletes for most of the course.

Table 1: Comparisons between the 3 CIM (‘22, 24’, 25’) marathons

This was my third time racing CIM, and I understood precisely what the course demands. Without strong quadriceps, CIM quickly becomes unforgiving. I trained accordingly, largely following the structure that had worked in previous buildups, but with several key adjustments. Most notably, I increased overall mileage, emphasized hill work, and leaned more heavily into sustained volume to better match the course profile and late-race demands.

3. Seven Years of Running (2019 - 2025)

Why I started Running (blame it on Martin!)

April 2019: Finishing my first half marathon (1:35:28), the most physical pain I had ever voluntarily endured.

I started running in February 2019 for three reasons, though I only recognized two of them at the time. First, my metabolism had quietly slowed as I entered my thirties. I was heavier than I realized, hovering around 200 pounds, and I needed change, quickly. Someone told me running was the most efficient way to lose weight, so I laced up and started. No, I wasn’t born running and I hated running prior to that. And for the most part still hate running. Second, my boss at the time, Martin, (an incredibly accomplished athlete) who was approaching his sixties, signed me up to run the Mahomet 5K with him on April 6, 2019. There was no scenario in which I was going to let him beat me. That alone justified what I generously called training. The third reason revealed itself later. My mother had mentioned, almost in passing, that life after thirty had a way of becoming monotonous. You settle into routines. Days blur. Years compress. You need something that interrupts the pattern, she said. Running became that interruption. What began as weight loss, competitiveness, and a nudge from maternal wisdom converged into a single practice. A simple act that quietly reshaped my body, sharpened my mind, and gave structure to time itself.

At the finish of my first 5k race (20:05) April 2019

Here, Martin (left) and I recap the race, with him explaining how he beat me. I listen carefully and take notes, knowing this would be the last time Martin ever beat me in a race. I have learned a lot about endurance sports from him!

Early Races and Lessons Learned

That first race turned out not to be a 5K at all, but a 10K. Two weeks before our planned race, Martin looked at me and said, “If the longest run you’ve done is five miles, then you can run a 10K.” And just like that, our first race together was changed.

He beat me decisively. Martin finished in 41 minutes. I came in at a painful 46 minutes, roughly a 7:30 pace. Despite having already lost nearly 50 pounds at this point, it was humbling. Two weeks later, on April 26, 2019, he beat me again at the Illinois 5K. He ran 19:28. I ran 20:05. That race marked the last time Martin ever beat me.

The very next day, April 30, 2019, I ran my first half marathon. It was the most painful thing I had ever done to myself at that point, finishing in 1:35:28 at a 7:16 pace. I tell this story because it marked the beginning of everything that followed. Within a year, running shifted from a tool for weight loss into something….some people call it obsession…well I am still defining what that is. I leaned heavily on my scientific training, treating each training cycle as a careful experiment, systematically recording outcomes and adjusting variables. In the process, I learned more about human biology than I ever did in my undergraduate coursework. I ran all over the world. Along the way, I met some of the most interesting people I have ever known through running and learned from them. I read relentlessly. But most importantly, I learned about myself.

At the finish of my second half marathon - Lake Waconia Half in June 2019 (1:34:53)

Even though I set a personal best that day, I realized just how hard running could be. I was completely spent. That expression is the face of someone struggling to hold a 7:15 pace.

4. My Marathon Journey

First Marathon and Early (a lot of) Mistakes

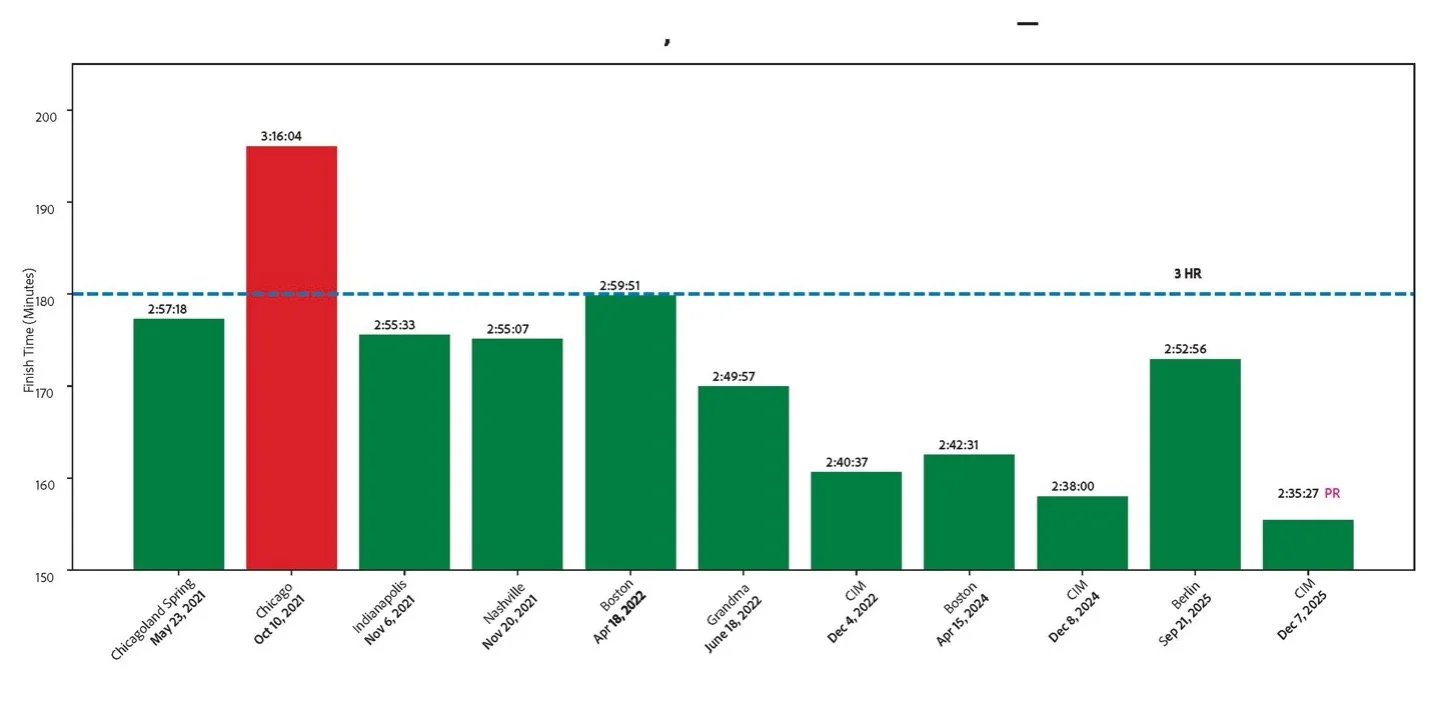

Figure 2: Seven years later, 11 marathons deep, including 3 World Majors. All but one were run under three hours. Along the way came countless half marathons, an unreasonable number of 5Ks and 10Ks, and multiple injuries, most of them earned through a healthy dose of stupidity. There was also a great deal of learning, many PT and chiropractor visits and one surgery.

At this point in my running journey, the marathon has become my distance of choice, though I am certain that will change with time. By 2022, I stopped racing anything shorter. The half marathon is a fun, fast race, but it ends too quickly. The marathon, by contrast, is uncertain. You are never entirely sure you will finish, though I have thankfully never recorded a DNF, despite coming close at the Chicago Marathon in 2021. I was fortunate not to rush into the marathon. Before attempting the distance, I focused on developing speed, steadily cutting significant time from my half marathon performance. I raced five to six half marathons before my first marathon, lowering my time from 1:35 to 1:21 (14 minutes). By then, I was confident that a sub-three-hour marathon was within reach. More importantly, I did not want to spend unnecessary hours on the course. That restraint, in hindsight, became one of the most important decisions of my development as a runner.

I ran my first marathon in May 2021 at the Chicagoland Spring Marathon. I didn’t know exactly what to expect, and my training leading into that race was incredibly haphazard—no consistent weekly mileage, poor structure, and I even ran a 20-mile long run exactly one week before race day. My nutrition plan for that race was just as bad. Still, I crossed the finish line in 2:57:18, under three hours. That result gave me immediate belief, because with that first marathon I qualified for the Boston Marathon. Later that year, I learned one of the hardest lessons of my marathon career at the Chicago Marathon. The race didn’t go to plan at all. It was extremely hot, humid, and windy, and I finished in 3:16:04. I was completely thrashed and ended up run-walking much of the race. It was humbling. Just weeks later, still deeply disappointed by Chicago, I bounced back with 2:55:33 at the Indianapolis Monumental Marathon, followed shortly by 2:55:07 at the Rock ’n’ Roll Nashville Marathon. In hindsight, running those two races so close together was a bad decision. I hadn’t fully recovered from Chicago, which showed a clear lack of understanding about racing and training. Because of that mistake, I picked up injuries that threatened my ability to race the Boston Marathon in 2022.

In 2022, I started to see the payoff of staying patient and learning from my mistakes. I ran 2:59:51 at Boston Marathon (April), gaining valuable experience on a challenging course. Then I broke into a new territory at Grandma’s Marathon (June), finishing in 2:49:57—my first marathon where I executed a negative split. That race showed me what was possible when everything came together.

Grandma Marathon June 2022 (2:49:57)

Later that year, I ran the California International Marathon for the first time and finished in 2:40:37. I had started working with a coach only two months before that race, yet I still ran nearly a 17-minute improvement from my debut marathon. That performance changed everything I thought I knew about racing and training. I was happy with 2:40:37, though part of me wanted to break sub 2:40. You could say it took me seven marathons to truly understand what marathon training actually entails. By that point, I had also finally dialed in my nutrition when racing.

After returning to Boston in 2024 and running 2:42:31, I went back to CIM in December with unfinished business—I wanted to run sub-2:40. In December, I lowered my personal best to 2:38:00, confirming that the progress I had made wasn’t a one-time jump. And I wasn’t too old to be competitive. Or hadn’t peaked yet.

Berlin Marathon September 2025 (2:52:56)

In 2025, I tested myself on a global stage at the Berlin Marathon, running a controlled 2:52:56. The hot conditions made fast running impossible, so I treated it more like a long run and embraced the experience. Then, on December 7, 2025, everything aligned—the temperature, the humidity, the training, and my hip finally functioning properly again after surgery. Back at the California International Marathon, I ran 2:35:27, my fastest marathon to date.

California International Marathon 2025 (2:35:27)

5. From 2:38 to 2:35: Comparison of my training of CIM 2024 and 2025. What changed in my training?

Why Sub-2:40 Is Hard (and Sub 2:30 even harder)

The most challenging aspect of running sub-2:40, or even sub-2:45 for us mortals, is that nearly every variable must be optimized: sleep (good luck!), nutrition, recovery, strength training, and overall load management. Performance at that level leaves little room for inconsistency. The greater challenge is doing all of this while sustaining a career, family life (toddler life), and other interests. Here, I share what I have learned so far and what I am still learning.

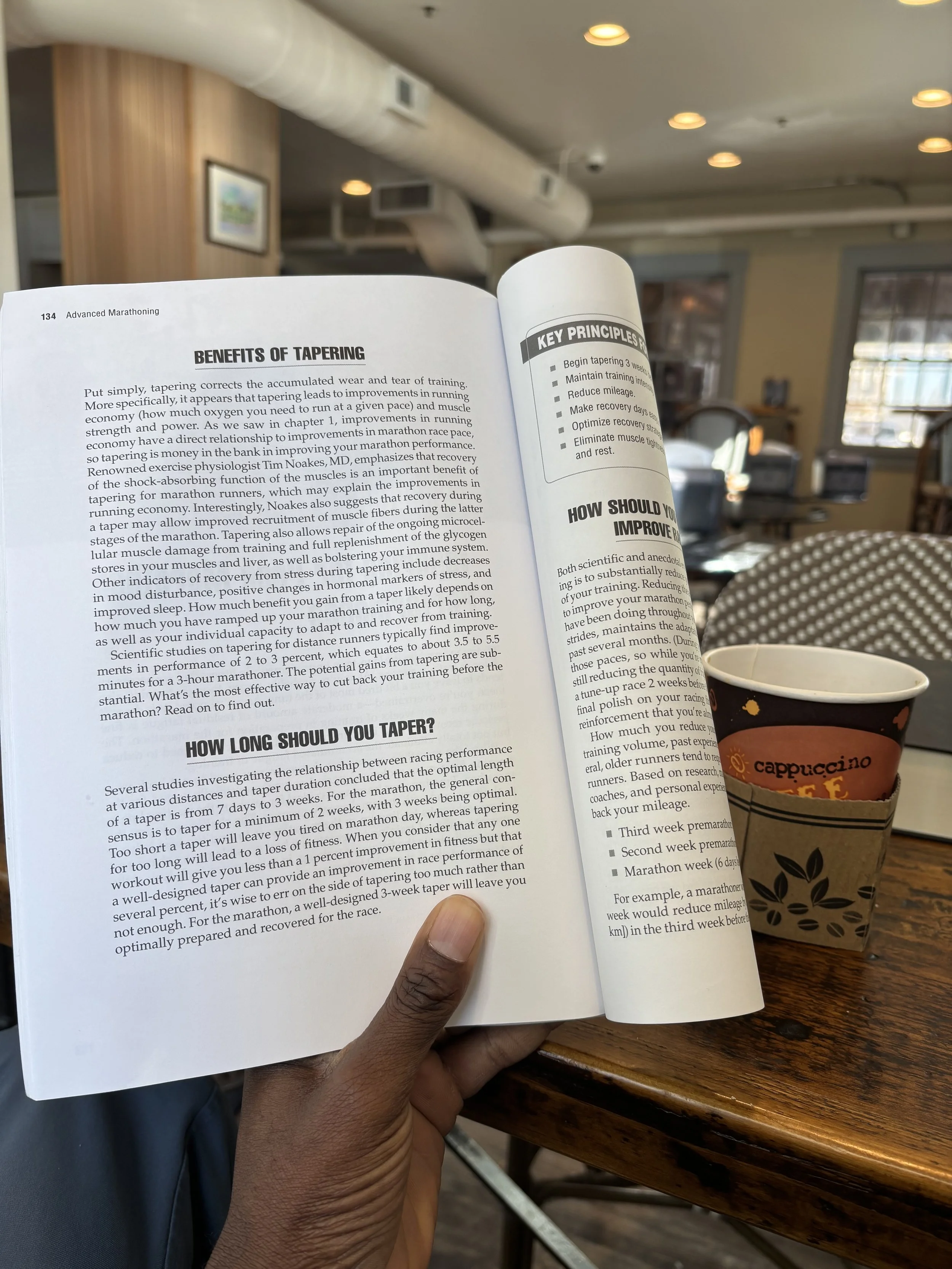

Like a Proper Academic, I read a LOT!

For my first CIM in 2022, where I ran 2:40, I worked with a coach (who has since moved on to now coach the big leagues (i.e Helen Obiri). For CIM 2024 and CIM 2025, I did not have a coach. That shift required learning how to coach myself, which turned out to be its own discipline, particularly when trying to move beyond a 2:40 marathon. At that level, effort alone is insufficient. You need the self-awareness to back off at the right time and the discipline to push precisely when it matters. Knowledge of body and recovery needs, nutrition, sleep, basically optimizing everything to squeeze a few minutes.

My education came from a small but serious library: Daniels’ Running Formula, Race Weight, The Science of Running, Run Faster from the 5K to the Marathon, and Advanced Marathoning. But self-coaching extended well beyond books. It meant working regularly with massage therapists, physical therapists, chiropractors, yoga instructors, and spending time under barbells in the weight room. In hindsight, the amount of time and energy invested outside of actual running borders on absurd, but it was necessary.

CIM 2025 Training Framework

The foundation of my CIM 2025 plan was Advanced Marathoning by Pete Pfitzinger (Fourth Edition). I discovered this book, fittingly, through the Advanced Marathoning subreddit r/AdvancedRunninghttps://www.reddit.com/r/AdvancedRunning/ . The framework became the backbone of my approach.

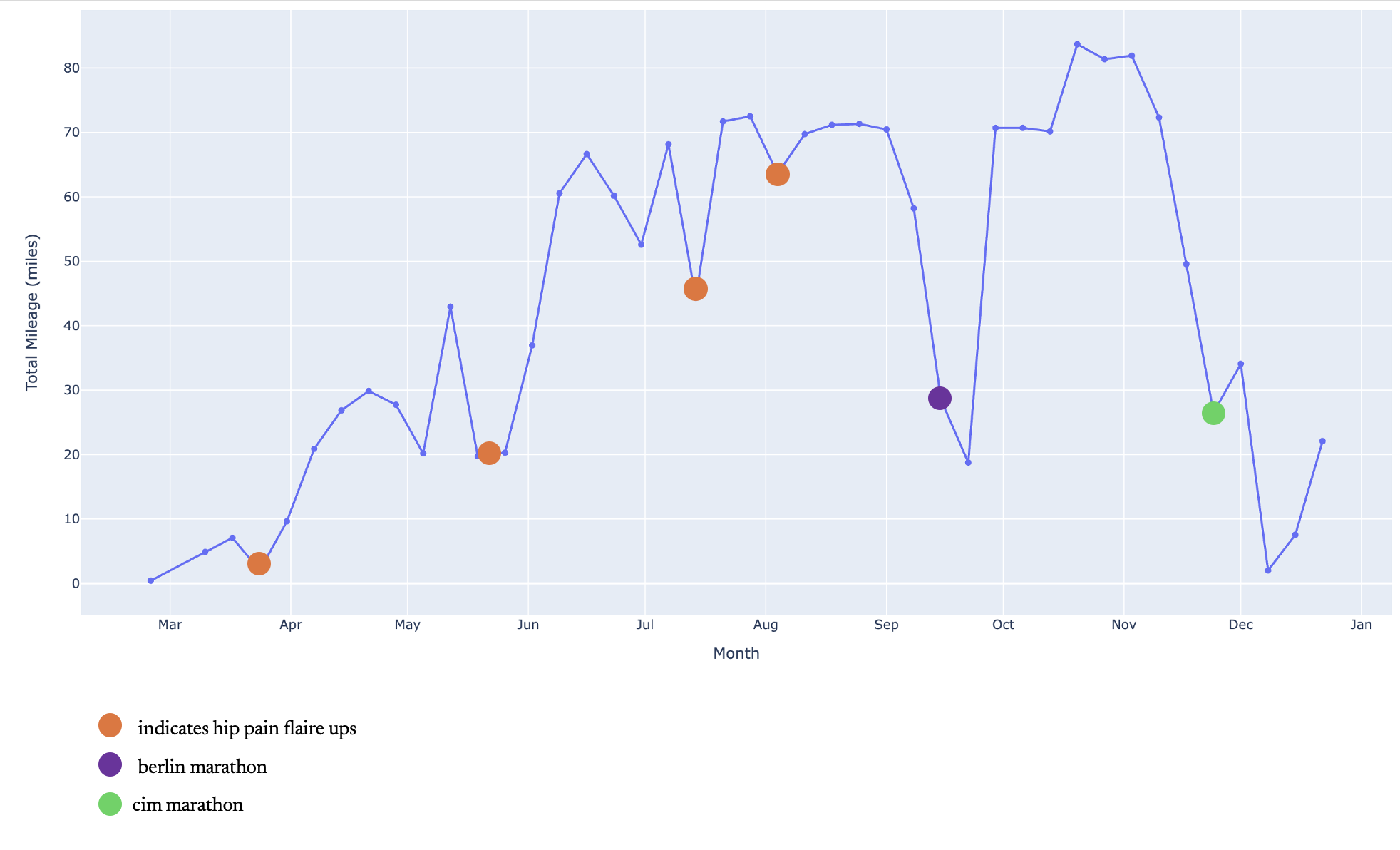

Timing, however, was the central challenge. For the first three months of 2025, I could not run at all while recovering from hip surgery. When I began rebuilding in early March, progress was uneven and often discouraging. Some weeks felt promising. Many did not. Flare-ups were frequent. Hamstring tightness appeared without warning. Hip pain rotated sides. Glute pain made periodic guest appearances.

Through both experience, literature and my PT, I learned about the kinetic chain: how an anterior pelvic tilt or hip dysfunction propagates dysfunction up and down the body. Some muscles tighten, others weaken, and alignment deteriorates quickly. My body was very much out of alignment. Consistent work with my physical therapist, Rebecca Brown (thank you), was essential. Week after week, she kept me functional enough to sustain long runs and maintain high mileage.

Progress was frustrating and anything but linear. I had originally targeted Berlin for a 2:35 attempt, but as training inconsistencies accumulated and quality workouts remained elusive, that goal became unrealistic. Fortunately, I had planned CIM 2025 as a backup. That decision proved critical. It allowed me to shift focus away from forcing fitness and toward healing, consistency, and gradual mileage accumulation.

Key training characteristics for the CIM 2025 build included:

Weekly elevation gain and loss averaging approximately 2,500 feet

A Pfitzinger-style structure with two long runs per week: one medium long run (12+ miles) and one traditional long run (16+ miles or longer)

Regular inclusion of VO₂ max and threshold workouts when physically tolerable

Peak weekly mileage of 84 miles per week

A two-week taper, consistent with my 2024 approach.

Pfitzinger-style structure (18 week/75+ MPW modified)

I followed an 18-week training program starting the week of August 4, 2025. Prior to that, I had been building my mileage gradually since March, starting at 2 miles per week and progressing to 70 miles per week by the end of July—a slow, five-month buildup.

Figure 3: The build-up had a few setbacks

That buildup, however, was interrupted four separate times by major hip flare-ups. Each time, I had to significantly reduce my weekly mileage, then patiently build it back up again (as shown in Fig. 3 by the orange circles). It was during the third flare-up that I realized I would not be able to run 2:35 at Berlin, as I had originally imagined. At that point, I was less than 12 weeks out from Berlin and still hadn’t completed any quality race-specific workouts or substantial long runs. So I made the decision to let go of the Berlin goal and instead shift my full focus to CIM. Making that decision removed a huge amount of pressure. I was able to train with less stress, listen more closely to my body, and back off before flare-ups escalated—rather than trying to force fitness that wasn’t ready yet. That reset ultimately allowed me to train consistently, stay healthy, and arrive at CIM in a position to run the race I was truly prepared for.

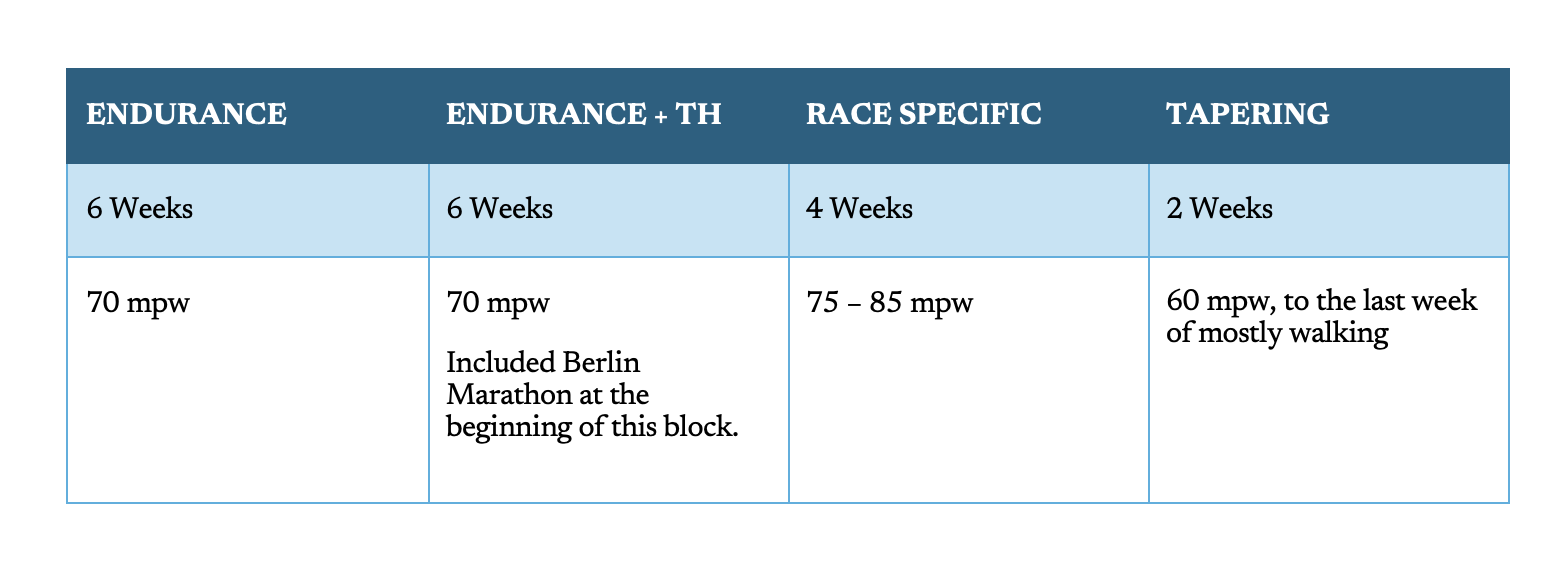

Table 2: CIM 2025 Training Block

The Pfitzinger approach structures marathon training into four progressive blocks that build fitness sequentially rather than all at once. Block 1 (Endurance) focuses on aerobic base development through high mileage, frequent medium-long runs, and controlled long runs, establishing durability and load tolerance. Block 2 (Endurance + Threshold) maintains volume while introducing lactate-threshold workouts to improve sustained pace efficiency and fatigue resistance. Block 3 (Race-Specific) sharpens fitness by layering marathon-pace work into long runs and workouts, training both physiology and execution under fatigue. Block 4 (Taper) reduces volume while preserving intensity, allowing accumulated fatigue to dissipate so fitness can fully express itself on race day. And this was the magic source! One of the hardest training blocks I have ever done but it did produce.

A friend once asked why I keep returning to CIM when there are so many other interesting marathons. The answer is simple: the scientist in me values consistency. Running the same course, with relatively predictable weather and a well-known hilly profile, allows for clean year-over-year comparisons. CIM provides a controlled environment to collect data, isolate variables, and measure real improvements in training and execution. The one variable I cannot control is age, which makes the experiment even more compelling. It will be interesting to see when, and how, performance eventually peaks and declines as I get older.

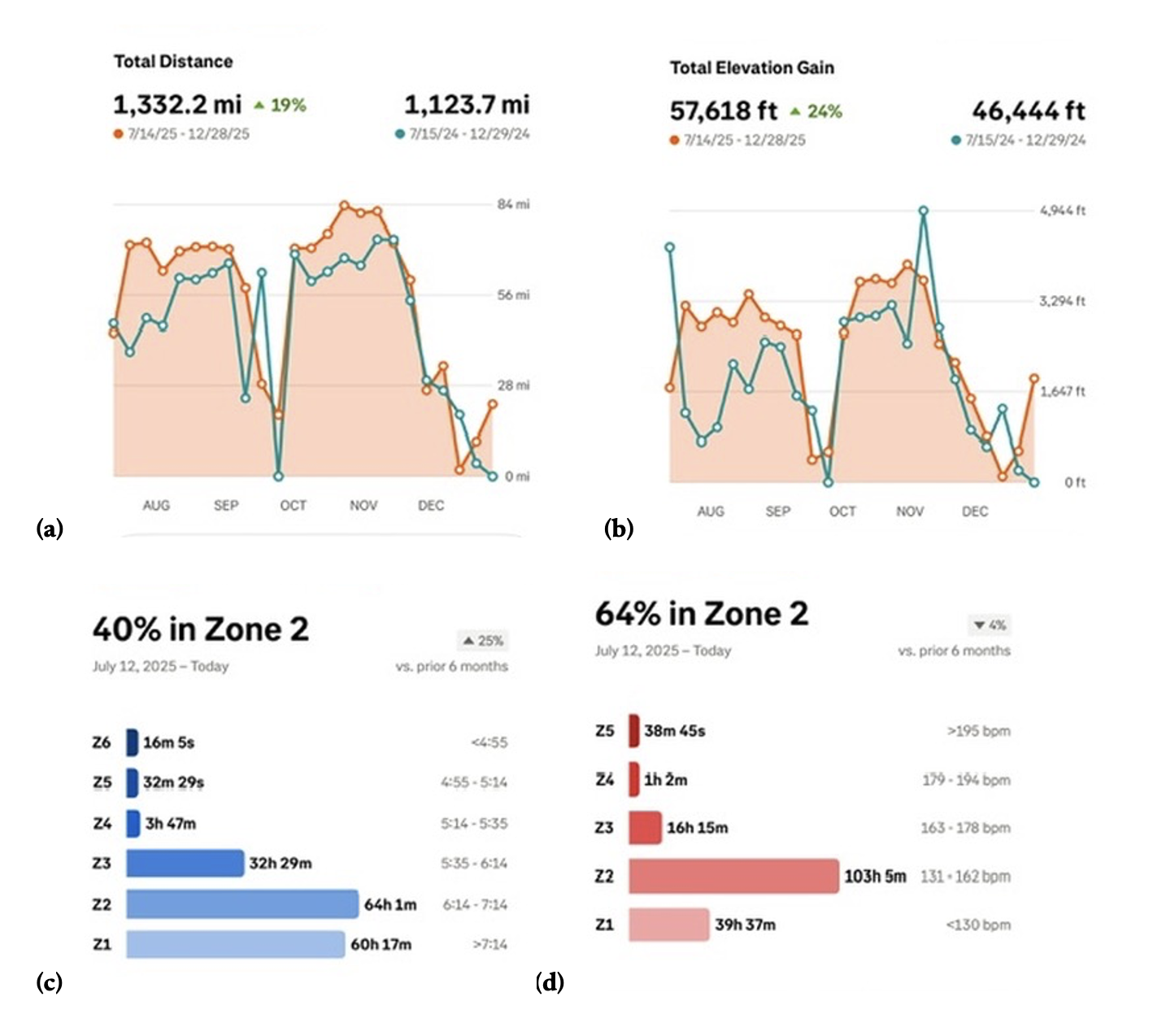

Training Volume Progression and Load Management (Fig. 4a below)

Over the 18-week CIM 2025 cycle, I accumulated 1,332.2 miles, a 19 percent increase over the 1,123.7 miles from the previous year. This reflected a deliberate decision to prioritize aerobic development and fatigue resistance.

Early in the cycle, from July through September, both builds followed a similar progression, with gradual mileage increases and planned down weeks to absorb the workload. The divergence emerged later. In the 2025 build, weekly mileage remained consistently higher from late September through November, settling into a steady upper range rather than oscillating sharply. Both cycles show a pronounced drop in early October. In 2024, this coincided with travel in Italy. In 2025, it followed the Berlin Marathon and a brief illness. The rebound in 2025 was faster and more decisive, as I aimed to preserve fitness. Recovery was facilitated by a controlled Berlin effort, as conditions were not conducive to a personal best.

Figure 4. Comparison of 18-week training blocks for CIM 2024 (green) and CIM 2025 (red). Data from my Strava.

(a) Total weekly mileage, peaking at 75 miles per week (mpw) in 2024 and 84 mpw in 2025.

(b) Total weekly elevation gain.

(c) Distribution of total time spent at different pace zones for CIM 2025.

(d) Distribution of total time spent in heart rate zones for CIM 2025. Showing 64% in aerobic zone.

The taper in December is sharp in both cycles. After weeks of focused intensity, accumulated fatigue becomes evident, and rather than maintaining volume, I intentionally slow down, incorporating more walking and rest. This approach differs from most conventional training plans, but it has worked consistently for me in both CIM 2024 and 2025. During race week, I run very little, allowing my body to fully recover and arrive at the start line feeling fresh and prepared.

Consistent Hill Work (Fig. 4b above)

Fig. 4b captures a key shift in my CIM 2025 build: the intentional integration of hill work. Total elevation gain increased from 46,444 feet in 2024 to 57,618 feet in 2025, a 24% increase. More important than the total was how that elevation was accumulated. In 2025, hills were incorporated consistently each week rather than concentrated in occasional extreme sessions. This approach played a direct role in improving quadriceps durability and late-race control on CIM’s net-downhill course. Notably, I experienced no quad pain during or after the race.

During the taper, I eliminated hill running entirely, aligning with reduced volume and an emphasis on resting.

Spend a whole lot of time foam rolling with my assistant

Long Run Structure and Marathon-Specific Fatigue

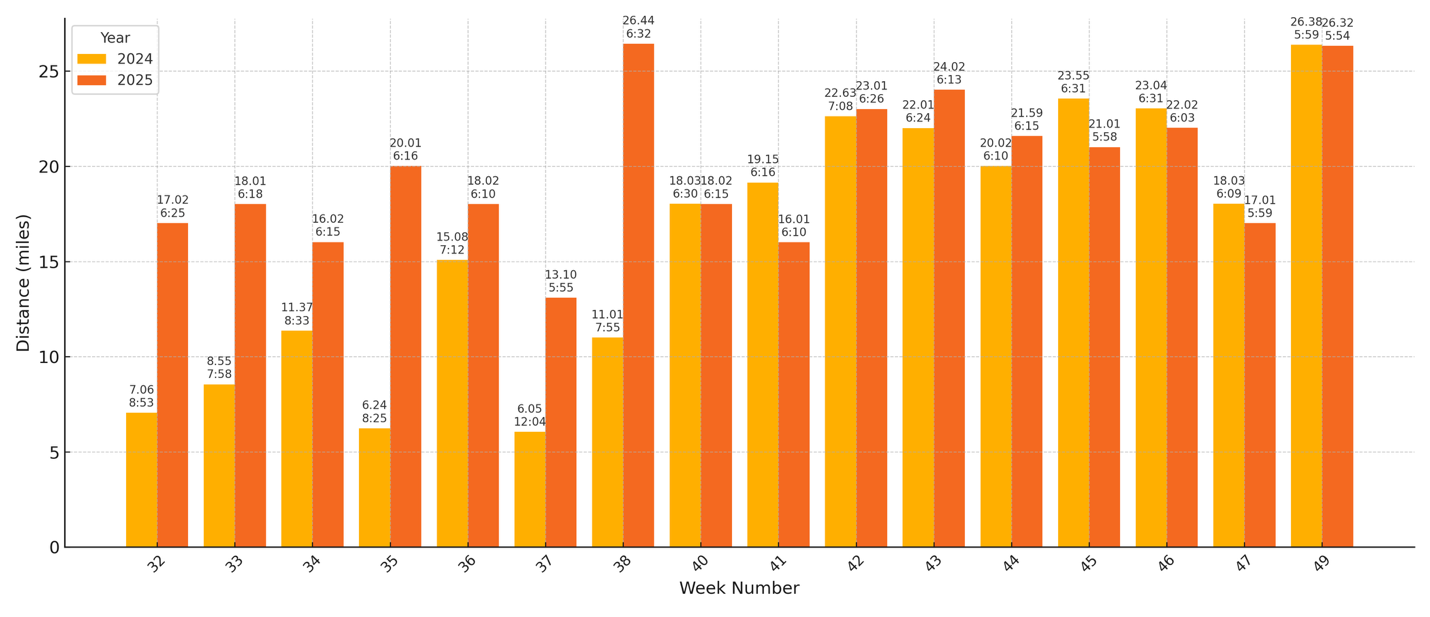

A defining feature of the CIM 2025 training cycle was increased emphasis on extended long runs of 18 miles or longer, executed at or near marathon pace, and in some cases faster. This approach was deliberate. The goal was to develop familiarity with marathon pace under fatigue and to rehearse the physical and psychological demands that emerge beyond mile 22.

My longest long runs outside of race efforts were 23 and 24 miles. Within these sessions, a substantial portion of the mileage was completed at or faster than 6:00 per mile, placing the effort squarely in marathon-specific intensity rather than purely aerobic endurance. These runs were less about distance accumulation and more about sustaining pace as glycogen stores declined and neuromuscular fatigue accumulated. And I used these long runs to master my nutrition uptake.

This structure proved critical for mastering late-race exhaustion. By repeatedly exposing myself to extended efforts at marathon pace deep into long runs, I was able to normalize the sensation of fatigue that typically appears in the final miles. On race day, the discomfort past mile 22 was familiar rather than destabilizing, allowing pace control and execution to remain intact through the finish.

Figure 5: Long Runs for the training season: CIM 24 (yellow); CIM 25 (orange). Please note, I am missing a long run between 47 and 49. That was my tapering week and I didn’t run a long run for both CIM 24 and CIM 25. Also note week 38 was the Berlin Marathon as an easy long run.

Carbohydrate Intake

One of the most consequential changes during this training cycle was a substantial increase in carbohydrate intake. Early in the build, I failed to recognize that I was significantly under fueling. Training volume and intensity routinely pushed daily energy expenditure beyond 3,500 calories, yet caloric intake lagged well behind output. The result was persistent fatigue, impaired recovery, and inconsistent training quality.

Midway through the cycle, I corrected this imbalance and deliberately increased overall caloric intake, with particular emphasis on carbohydrates. The impact was immediate and measurable. Recovery between sessions improved, fatigue diminished, and my ability to absorb higher training loads increased.

A key component of this shift was the regular consumption of ugali, a Kenyan staple made primarily from maize flour. Its simplicity, high carbohydrate density, and ease of digestion made it an ideal fuel source. Once incorporated consistently, often daily, it became a cornerstone of my fueling strategy and played a significant role in supporting sustained volume and intensity through the remainder of the build.

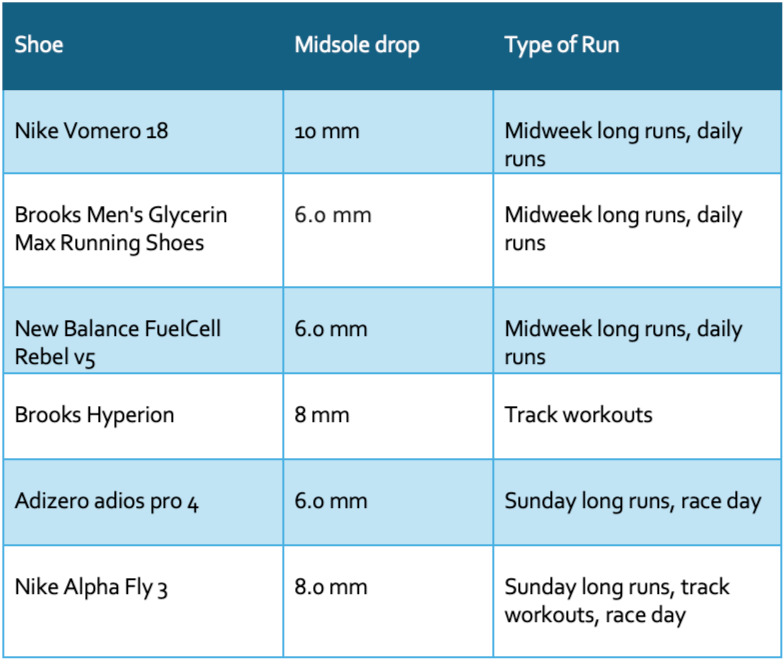

Shoe Rotation and Injury Implications

A question I am often asked is what shoes I use. What follows is my personal strategy, with an important caveat: these choices work for me and may not work for everyone. Footwear is deeply individual. In my case, two factors dominate my decision-making. First, I run extensively on concrete, which makes cushioning non-negotiable. Second, I have flat feet, which introduces its own set of biomechanical considerations.

Shoe rotation in practice: here I’m wearing the Brooks Glycerin Max to handle the uneven impact of cobblestones.

Shoe rotation was another deliberate part of my training. On many days, particularly during my run commute, I would use one shoe for the run to work and a different shoe for the run home. Over the course of a week, I rotated consistently to vary mechanical loading and ensure that different muscles and structures in the foot and lower leg were stressed in slightly different ways.

Because much of my run commuting was done on concrete sidewalks, cushioning was a priority. Shoes such as the Nike Vomero 18, Brooks Glycerin Max, and New Balance FuelCell Rebel v5 formed the backbone of my daily and midweek long runs, providing protection from repetitive hard-surface impact. Faster sessions and race-specific efforts were reserved for more responsive shoes, including the Brooks Hyperion, Adizero Adios Pro 4, and Nike Alphafly 3.

Table 3: Shoes worn for the 2025 CIM training block

One variable I did not evaluate carefully enough during this training cycle was midsole drop and its cumulative impact on lower-leg mechanics. Several studies suggest that higher heel-to-toe drop shoes can maintain the calf musculature in a shortened, tensioned state, potentially increasing strain over time. In retrospect, this aligns closely with my experience. Throughout much of the season, I struggled with progressive calf tightness and intermittent shin splints. These issues culminated at mile 21 of CIM, when my right calf began to fail, producing sharp pain with each step for the remainder of the race.

Post-marathon, the unresolved calf tightness evolved into plantar fasciitis, confirming that the issue was not isolated to race day but rather the result of accumulated load over the entire training block. While shoe rotation likely helped distribute stress, insufficient attention to midsole drop across shoes may have contributed to excessive and chronic calf loading. This is an area I plan to study and adjust more deliberately in future cycles.

Mastering the Run Commute

I have been run commuting for years, but this season I optimized it. Most weekdays, I ran to work in the morning and home in the evening. Running seven miles from West Roxbury to Back Bay took 45–54 minutes, compared to a 75-minute train ride. I saved time, eliminated passive commuting, and accumulated meaningful mileage without adding hours to an already full schedule.

The run commute gave me flexibility and control. Midweek long runs of 13–16 miles were built by extending one or both legs, using preplanned route variants that allowed me to dial mileage and elevation based on the day. One favorite route included the final ten miles of the Boston Marathon course and the Newton Hills, running early to avoid traffic. Logistics were critical: two lockers (one of running clothes and one for work clothes) at the work gym, a weekly Sunday reset bringing fresh work clothes and food for the week, a dedicated commute bag, and basic recovery tools the office. With high mileage, a demanding job, and a toddler at home, the run commute made training sustainable. It also created clean mental boundaries: focus on the run in the morning, leave work behind on the way home, and arrive present for recovery and family.

6. Lessons for Next Season

There are several lessons I carry into the 2026 season. I plan to run the Boston Marathon at a more controlled, relaxed effort, likely around 2:45, and place greater emphasis on a focused build toward Berlin in September 2026. Is a 2:28 in Berlin possible?

One of the most important lessons from this season is that I allowed muscle tightness to linger longer than I should have. That decision caught up with me late in the CIM race and again post marathon. Going forward, regular bodywork cannot be optional. A massage therapist needs to be part of the plan, especially beginning in the second block of a four-block training cycle, when cumulative fatigue starts to rise.

Hip health remains a priority. I underestimated the impact of limited hip mobility, and it affected more of my running than I initially realized. I also neglected thoracic mobility, something I am now learning plays a meaningful role in posture, arm swing, and overall efficiency. These gaps are fixable, but only if addressed consistently. Next season, mobility work, particularly for the hips and thoracic spine, will be non-negotiable.

Finally, I need to be more disciplined about fundamentals that are easy to dismiss when time is limited. Running drills, strength maintenance, and prehab work often feel optional in the moment, but they are critical at this level. As the margins narrow, ignoring small things becomes costly.