Rainbow Row

Rainbow Row is a celebrated line of thirteen pastel-colored, Georgian-style houses at 79–107 East Bay Street in Charleston’s historic district. Among the city’s most photographed landmarks, it is admired for its soft hues and layered history. Built between the 1740s and 1845, these buildings once functioned as merchant shops at street level, with living quarters above, facing what was then a busy and commercial waterfront.

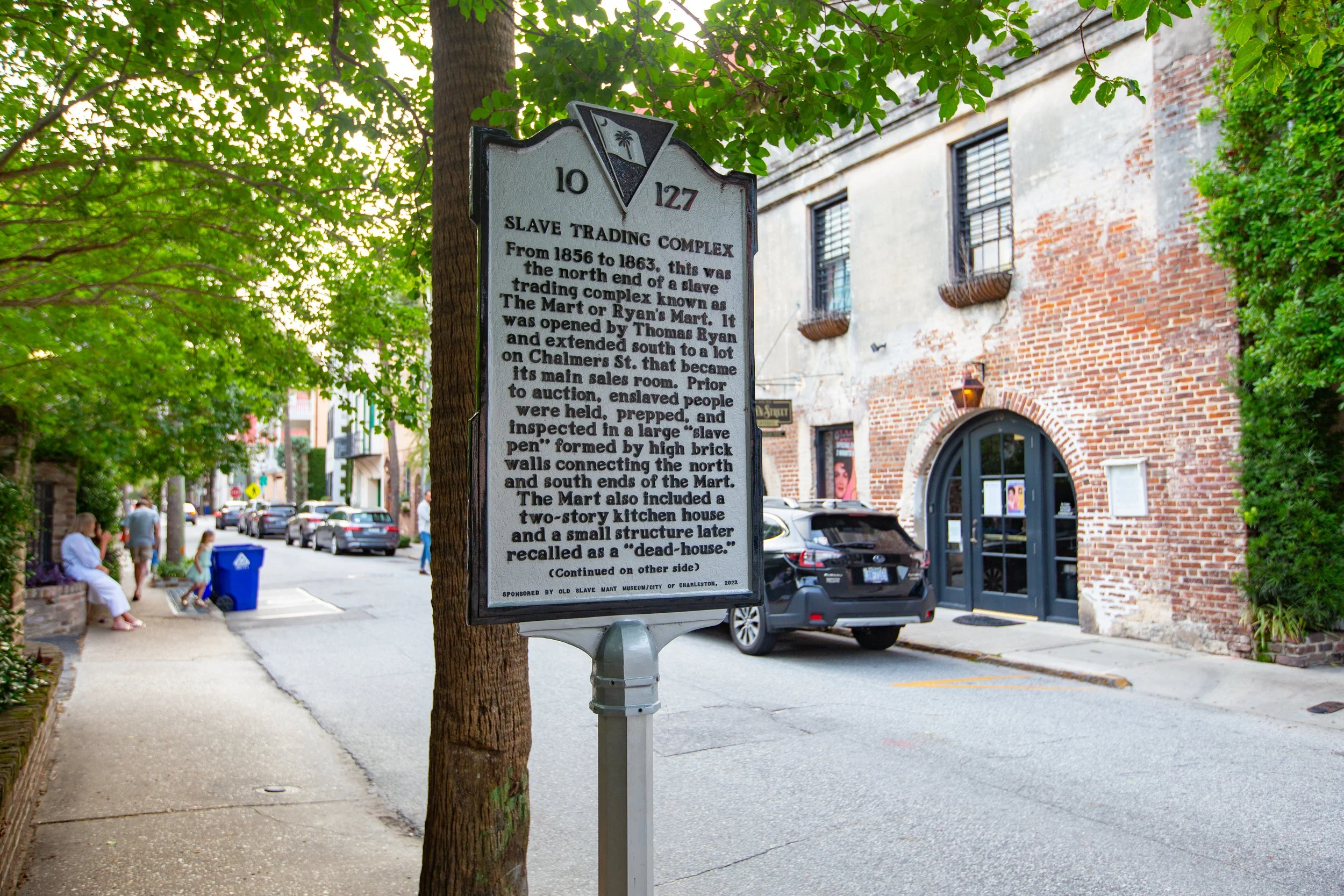

Chalmers Street in Charleston, SC, is famous for the Old Slave Mart Museum, located at 6 Chalmers Street, marking a site where enslaved people were held and sold after public auctions were banned, becoming a crucial part of the domestic slave trade, with its legacy now preserved as a museum telling the brutal history of slavery and auctions in the city

Cabbage Row was once a crowded tenement primarily housing African American families of freed slaves, where residents sold cabbages from their windows, giving the row its name. In the early 20th century, it became known as “Catfish Row” after DuBose Heyward used it as the setting for his novel Porgy, which later inspired George Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess.

Bedon’s Alley is a narrow historic lane in downtown Charleston, tucked behind Rainbow Row near East Bay Street. Dating to the 18th century, it once served as a service passage for nearby homes and warehouses, including access to slave quarters and work spaces. Today, its pastel walls and quiet, enclosed feel make it a small but powerful reminder of Charleston’s layered history and one of the city’s most photographed hidden corners.

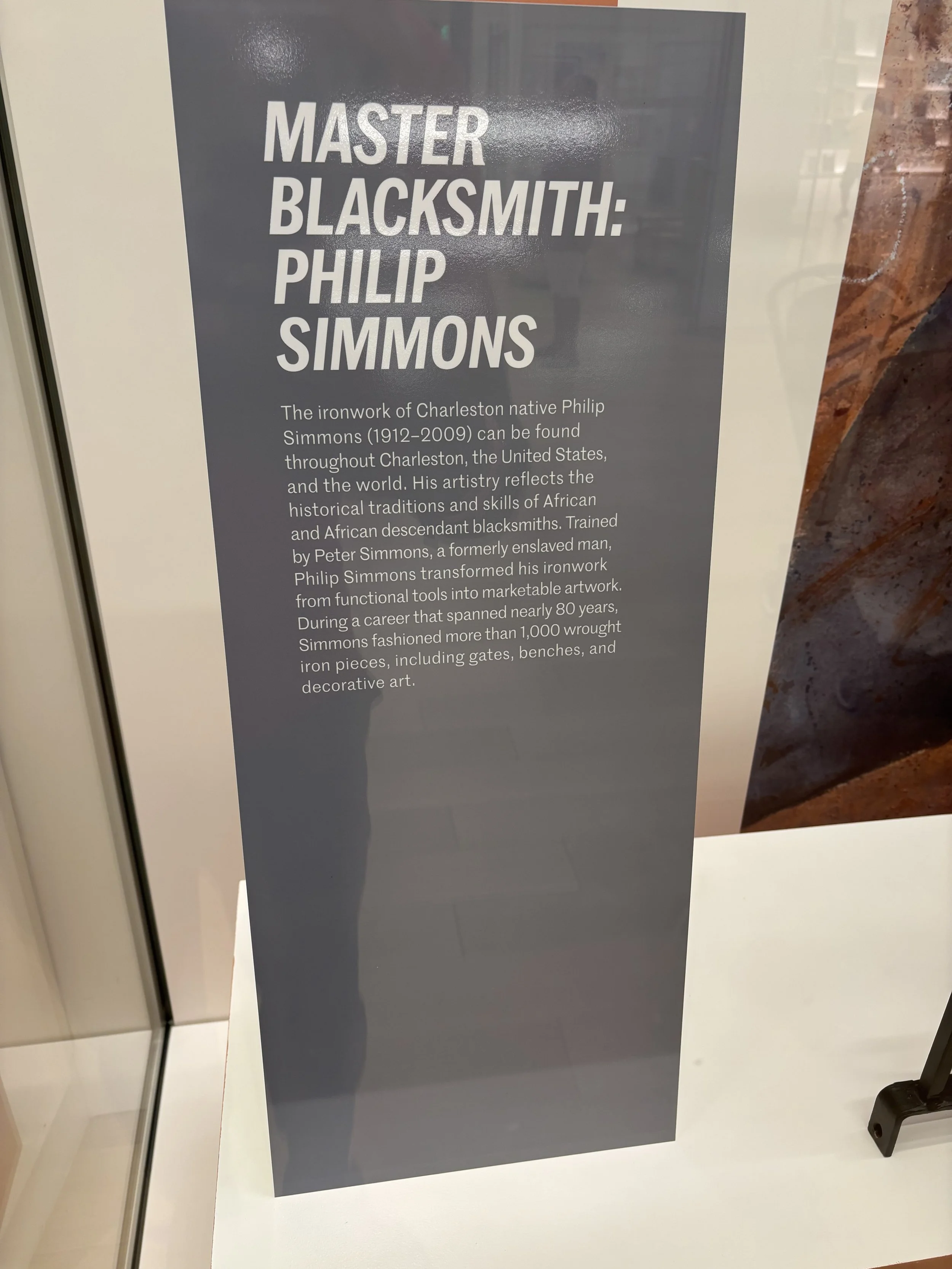

Philip Simmons

The legacy of Philip Simmons in Charleston lives on through ironwork that quietly shapes the city’s visual identity and cultural memory. Born into poverty and largely self-taught, Simmons transformed wrought iron from a functional trade into an expressive art form, crafting gates, fences, balconies, and sculptures that balance strength with elegance. His work draws from African American traditions, Lowcountry history, and personal imagination, turning everyday materials into symbols of resilience and creativity. Beyond the physical pieces scattered throughout Charleston, Simmons’s true legacy is also educational and communal. He mentored younger generations, shared his craft openly, and ensured that Black artistry and labor were recognized as central to the city’s heritage, not a footnote to it.