Keeper of the Gate | Charleston

Philip Simons

Keeper of the Gate

What makes Charleston—founded in 1670 as Charles Towne after King Charles II—so charming? Is it the flower boxes perched perfectly on every windowsill in the French Quarter or South of Broad? The ornate wrought-iron balconies curling like black lace? The expansive porches, swinging benches, and manicured green gardens of its grand Southern homes? Or maybe it's the independent boutiques that stubbornly resist the Walmartization of America. Whatever the secret sauce, Charleston has buckets of it.

Wrought iron balconies adorn Charleston buildings

Outside of Old San Juan and Carmel-by-the-Sea, Charleston wins, hands-down, the title of "prettiest little city" I’ve run through in America. It feels like a European village air-dropped into the American South—quaint, elegant, and rich in contradiction. Nearly every street bears a plaque that doesn’t flinch from its past. It’s a city with charm, and complexity, and a strange willingness to admit both.

Charleston

It feels like a European village air-dropped into the American South—quaint, elegant, and rich in contradiction.

On this particular run—an ambitious 8-mile loop—I wanted to go beyond the aesthetic and understand the story behind Charleston’s beauty. I became fixated on the wrought iron—those intricate gates and balconies adorning homes like jewelry. It turns out that much of it can be traced back to one man: Philip Simmons in the 19th Century. An African American blacksmith often called Charleston’s “Keeper of the Gate,” Simmons was less a tradesman than a sculptor of stories. Born in 1912 on Daniel Island and raised by his grandparents, he began his apprenticeship at just thirteen. Over a career spanning nearly eight decades, he transformed raw iron into poetry—wrought curves, spirals, egrets, vines—that now grace nearly every corner of Charleston.

Cross and Egret Gate

So, this run became a tribute. I began in the French Quarter at St. Philip's Church, pausing at one of Simmons’ masterpieces. From there, I followed Church Street to Michael’s Alley, where I found the “Cross and Egret” Gate—delicate, dignified, unmistakably Simmons. I jogged through the cobbled streets, sweat clinging in the Southern humidity, tracing his work like a map.

Plaques Around Charleston

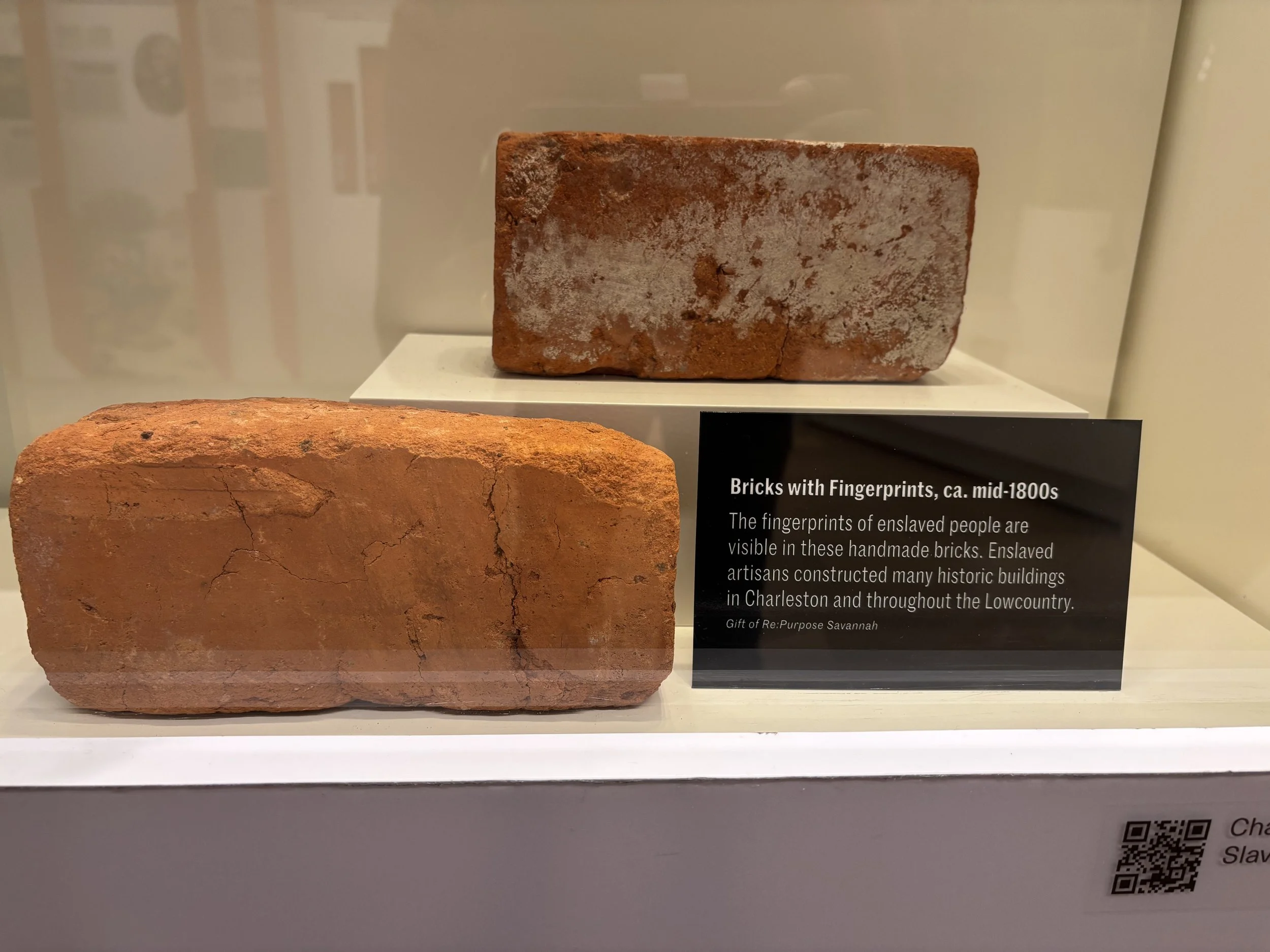

Charleston’s wealth—at one time the richest of the colonies—was built on enslaved backs. That truth is etched into its bricks, literally. You can see those fingerprints at the International African American Museum and feel the weight of that history at the Old Slave Mart Museum, built in 1859 as a slave auction house. It’s estimated that 90% of African Americans can trace their ancestry through this region. Generations later, Black artisans like Simmons continued to beautify Charleston with skill, grace, and love, refining the city’s elegance with each gate, and balcony they forged.

Bricks with Fingerprints

On exhibition at the International African American Museum, located at Charleston’s Gadsden’s Wharf—a major disembarkation point during the transatlantic slave trade.

Then I ran to the East Side, once home to many of Charleston’s Black craftsmen. Near the end of my loop, I passed Simmons’ old workshop on Blake Street. It now stands ivy-covered and weary, a relic in the shadow of a city it helped beautify. Ironically, as the city continues beautifying itself it pushes away those who created the beauty. Phillip Simmons might be called the “Giver of Gates,” but in a cruel twist, those same gates now seem to close gently yet firmly behind the artisans who forged them through gentrification.

Philip Simon’s Workshop

Now stands ivy-covered and weary, a relic in the shadow of a city it helped beautify.